Our Secret Cold War

© Copyrighted November 2003 – Ray M. Thompson

I remember it like it was last year, but it was really over 50 years ago now... A bunch of very non-military college-age kids were serving in the United States Air Force Security Service (USAFSS). Our unit was the 6910th Security Group, based at a former German air base just outside the beautiful little Bavarian town of Landsberg am/Lech. Our daily jobs were part of an Air Force intelligence mission and highly classified. Although far from home and in the land of a former enemy, most of us privately gave thanks that we were not with our USAFSS counterparts in Korea; we knew we had a plum assignment in Bavaria. (Master Sgt. Jim Schuman, who had served in Korea, was assigned to our section. He told us of working with Korean translators so near the front that they became overun and had to be evacuated by air. His translators were evacuated before some of the GI’s, because of the sensitivity of their jobs.) We spent our spare time chasing German frauleins, drinking German beer, snapping our German cameras, traveling throughout Western Europe and dreaming about getting out at the end of our 4-year enlistment.

On the other hand, we were all very serious about our jobs, part of a large intelligence gathering enterprise. Because of the sensitive nature of our jobs, we were forbidden to take leave in the border area near the Iron Curtain, but listening to Russian radio signals across that border was our job. The truth is, we were hand picked for our jobs. Not that we knew anything about what we were getting into, but many of us had college degrees or other aptitudes that filtered us into the USAFSS. (I do know what got me in—a brand new BS degree, and because I had a ham license and knew the Morse code!) We received on-the-job training in communications intelligence (COMINT) at Brooks AFB in San Antonio, Texas. We were then sent worldwide to work in a secret part of the Cold War. USAFSS RSM Units (Radio Squadron’s Mobile) were stationed from Alaska to Korea, and from Scotland to North Africa…

Yeah, we were kind of a smart-alec bunch of kids, but we did our jobs well. Our work became most serious when the Russians made some move or change in their military operations, changes we were often the first to detect. These changes were usually preceded by changes in the Russians’ radio call signs and frequencies—operational details which we spent months tying to specific military units (ground and air), thus defining their military organizations, or “order of battle.” The Russians changed their call signs because they knew we were listening and that the change would confuse our monitoring efforts. (Of course, the Allies did the same thing.) Usually these changes turned out to be military training or maneuvers, but the Allies always had to treat them as the real thing—perhaps an invasion of Europe. Our monitoring could bring the entire Allied Forces to a silent alert. Soon their listener’s knew that we knew—this was the secret cold war. These were the days we earned our stripes…

We were called to duty (often rousted out of bed) at the first hint of a call sign change, and worked around the clock until the crisis was over. (Or, if an alert were ever the real thing, until we were told to burn our records and evacuate!) We worked at wall-sized maps of the USSR, labeled TOP SECRET. These “alerts” called for urgent and coordinated efforts by all sections, beginning with the Radio Intercept Operators [1], who listened to the cacophony of static and radio signals in Morse code and copied them down with unbelievable accuracy, using typewriters equipped with the Cyrillic alphabet. Then, there were the Crypto Analysts, who dealt with the complexities of encoded messages and call signs. There were also airmen trained as Russian Language Analysts, whose job was to translate clear text and voice messages. We had Radio Direction Finding (RDF) Operators who tried to fix the positions of the Russian transmitters. Finally, there were the Radio Traffic Analysts, whose job was to learn as much as they could from the “headers” of the messages, i.e., the parts of the message that were not encrypted. (My knowledge of Morse gave me an edge in figuring out “garbles” in the intercept “chatter rolls” we received from the RSM’s!) All of our jobs depended, to some degree, on mistakes made by the Russian radio operators. All military operators are taught rigorous rules of “radio discipline” designed to prevent such mistakes, but they do happen, and can reveal information the enemy should not know!

Secrecy was all-important in our highly sensitive work. We were warned regularly, in security lectures we were required to attend, that we could not describe or discuss our work in any way, with friends or family. In fact, we were strictly forbidden to discuss our work with each other outside the secure buildings where we worked. Even within our secure compounds, the various sections where we were assigned were isolated from each other. So, even though we might bunk together, at the office we had no contact with buddies in another section unless we had “a need to know.” To my knowledge, among those I knew, we were faithful in observing all these security rules. (When we returned to civilian life we continued this secrecy about our jobs, although our friends and families sometimes thought we made too much of our “secret jobs.”)

I especially remember one security lecture, while in training at Brooks AFB that made a lasting impression on me. One morning at breakfast, we were shocked to read in the newspaper (“The San Antonio Light”) a story about our training at Brooks. The story pretty well told exactly what we were being trained for in our “secret compound” on the base! Knowing this story would undermine the security lectures we were receiving, the CO called a meeting of everyone as soon as we reached the office. His message to us went something like this:

“We know the newspaper has this story and runs it periodically—it sells newspapers! You bought one, didn’t you? We have taught you that the elements of this story are certainly no secret to our enemies—they know of your jobs and your training and are training their operators to defeat your efforts! We are training our communications personnel to protect our communications from their analysts! What our enemies don’t know—NOW HEAR THIS!—is how SUCCESSFUL we are! Do you see that if you brag about your “secret work” or hint at “the importance of your job,” or say anything at all—you may infer something about the success of our efforts? That, gentlemen, is why the only way to have security is simply to never, never, say anything about your jobs, to anyone.”

So, did we help keep the Russian bear at bay? Yes, certainly we helped, but I still cannot reveal any specifics about the successes or failures of our efforts. The fact is, as “worker bees” in a huge intelligence organization, we were never told the ultimate value of the information that we gathered. Why? Because we did not have “the need to know.”

Well, here we are 50 years later, and I’m writing this bit of personal history about my “secret job.” Why? Because the work we did in the early 1950’s has little bearing on the world of COMINT today. Because the means, methods, and technology that we used (Morse code for goodness sake!) [1] are now so outmoded as to be only a page in COMINT history; we worked with card files, not computers! Because we have been superceded by five decades of COMINT gathering secrets that I know nothing about. Because much of our early work has now been declassified and is the subject of numerous books. movies and “discussions” on the internet about what we did and how we did it, so long ago. [2] [3] (Because I know there were some who lost their lives in the intelligence war—USAFSS airmen who flew secret airborne monitoring missions (SIGINT) against the Russians and were shot down; I’m especially proud that their story is finally being told. [4] Because I’ve relished remembering and reliving my experiences with a great group of former 6910th airmen that I organized on the Internet in 1997— The USAFSS 6910TH 5O’s GROUP. Our association includes our web page http://www.usafss6910th.org, a Yahoo e-mail-list (hosted by myself), newsletters [5] and two great reunions (in 2000 and 2002, planned and hosted by Bill Purser). And finally, because in my dotage, I have longed to share something of what we did with my family and friends, and to say that we took great pride in doing it well. And, if called on, we would do it again! The USAFSS motto was: “Freedom Through Vigilance”

- --

A/1c Ray M. Thompson, AF18410468 - Radio Traffic Analyst Aide -

Version 8 – July 2008 -

Footnotes:

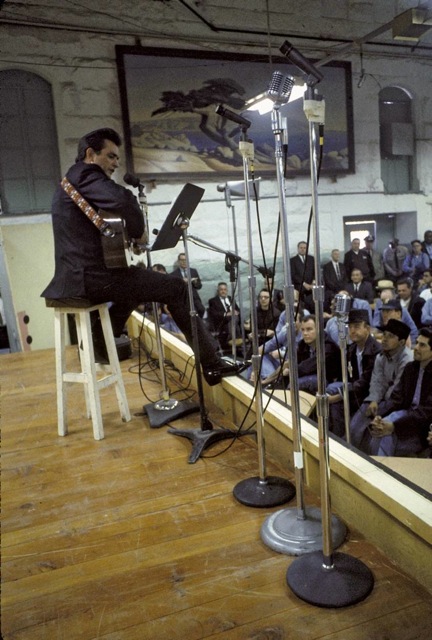

-[1]- We love to tell this story: one of the Radio Intercept Operators at Landsberg AFB was a guy named Johnny Cash. And, yes, he was the Johnny Cash, destined to become a C&W super star. Read Johnny’s own account of his USAFSS experiences in his biography “Cash,” (written with Patrick Carr), Harper Paperbacks 1997 - “Arkansas Ditty Bopper” Poem and notes about Johnny Cash by Mark Wilson

-[2]- I recommend Body of Secrets, by James Bamford, Doubleday 2001-

-[3]- Try these in Google: USAFSS, AIA, COMINT, SIGINT, ELINT

-[4]- Read: Untold, in-depth history of USAFSS with an overview of ESC, AFIC, AIA and AFISRA, by a member of USAFSS, Larry Tart; http://larrytart.com/FTV/ftv.html (It’s been a privilege to have Larry in our USAFSS 6910th 50’s Group mail list.)

-[5]- Newsletter No. 4 – September 2000, USAFSS 6910th 50’s Group, 142 pages, published by Ray M. Thompson

-[6]- Wikipeida Listing for USAFSS

Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison - January 13, 1968